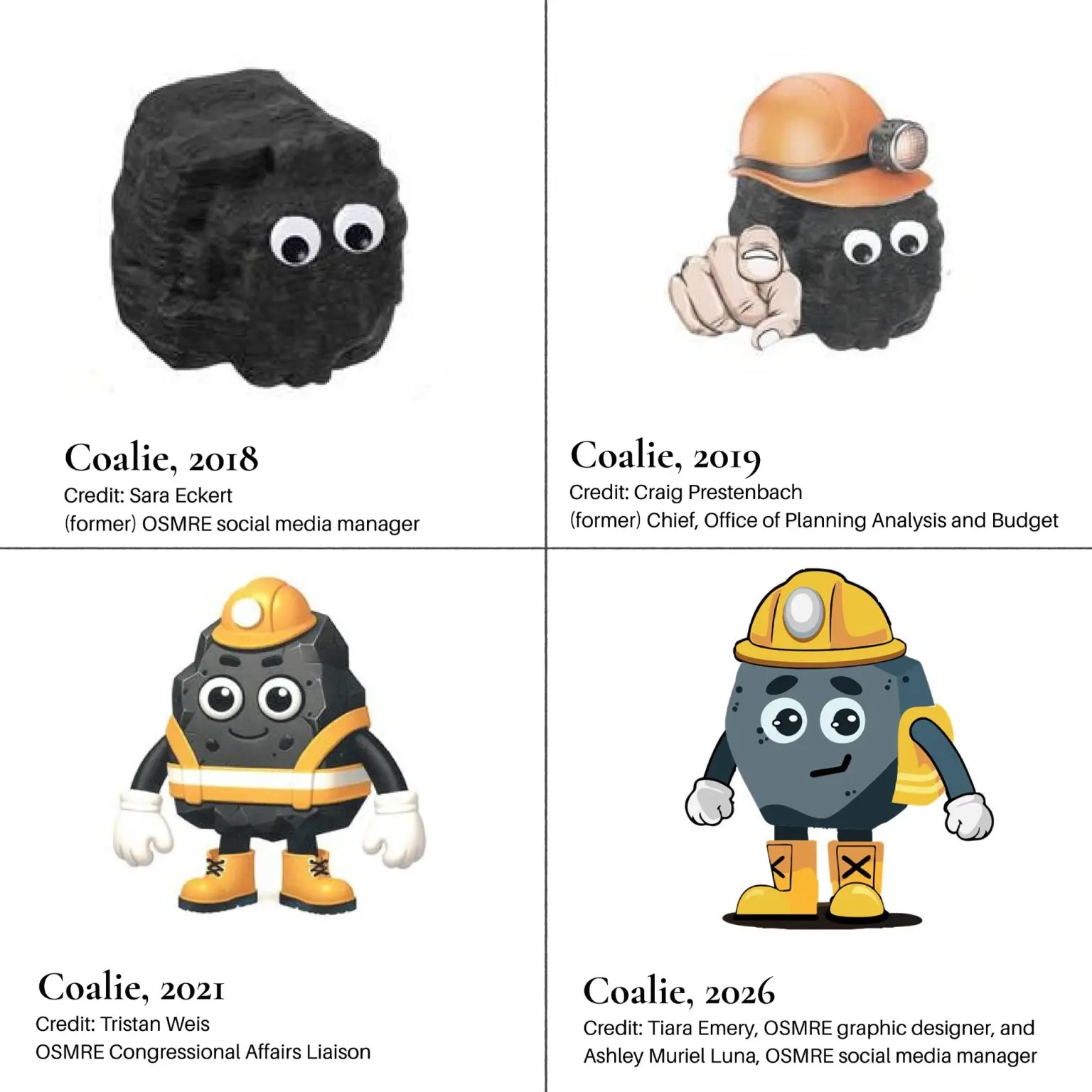

Kate Yoder at Grist has exhumed a brief history of “Coalie,” a US Dept of Interior’s new-not-entirely-new mascot for “Beautiful, Clean Coal.”

As it happens, I just started Benson Bobrick’s Labyrinths of Iron: Subways in History, Myth, Art, Technology, and War (NYC: Morrow, 1981), which so far is great: a bit florid maybe, but the scope of his research is amazing, and his writing is quick, vivid, and surprising to the point of astonishing. Everyone know Blake’s phrase “dark, satanic mills,” which has become an obstacle to having any realistic sense of just how monstrous the second Industrial Revolution was. Bobrick’s Chapter 3, “At the Brink of Chaos,” does a solid job not just of fixing that but of pursuing it back in time:

Three thousand years before Christ incessant copper and tin mining had exhausted the forests of Egypt’s Fertile Crescent, leading one modern historian to conclude: “The price of maintaining a culture built on metals is high: it means, eventually, complete collapse. The depletion of the timber range upsets the natural balance, and the land that began as an arboreal abode for foraging men and beasts finishes as a useless wasteland scourged by the sun and scoured by floods, with an interesting past but no future. To eat the apple of metallurgical knowledge is a sure way to close the gates of Paradise.” By the mid-sixteenth century this process was being repeated in Europe. Georgius Agricola, in his account of metal mining in Germany, foresaw the full extent of the threatening disaster: “…when the woods and groves are felled, there are exterminated the beasts and birds, very many of which furnish pleasant and agreeable food for man. Further, when the ores are washed, the water which has been used poisons the brooks and streams, and either destroys the fish or drives them away.”

And into the future as well:

Indeed, it is a large question whether this is not, after all, the critical fact in our story: that as life above came to resemble life below, modeled on the mine, it became possible for people to reconcile themselves to living in the Underworld. With our late twentieth-century toxic wastes, vehicular fumes, and threatened nuclear fallout, we still maintain this sad psychological adaptation, though its original cause has by now almost vanished from memory.

Reading this lends new depth to Marx and Engles’s famous line all that was solid melts into air. I’m still looking for an economic way to express my twentieth-century corollary about the rise of aviation and its impact: all that was air becomes solid will have to do for now.

So… Coalie. Coalie? Debates about coal (to the extent there even are any) end up like most such things in US culture: straddling an arbitrary divide between two artificial tropes, in this case sooty Appalachian coal miners and a radiantly clean future. As of 2025, there were about 35,000 coal miners in the US, which is about halfway between gun suicides (27,000) and car deaths (41,000) — clearly not a number the US bothers itself with much.

The Grist article traces how “Coalie” morphed from a tongue-in-cheek mascot whose intent was to make the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (read that name twice) a bit more accessible. Under Trump, like so many government employees, Coalie is being repurposed to push the retrograde, revanchist fantasies of an ambecile whose cultural-cognitive framework froze around the same time Coal Miner’s Daughter was in movie theaters — that is, a time by which coal mining had already become as much nostalgic fiction as practical fact. That compound nostalgia — Making America Great Again by pining for the last time we tried to Make It Morning in America Again — might account in part for how elusive it all feels this time around.

Coalie’s quick evolution, from 2018’s pre-gendered lump of coal with googly eyes to 2026’s man with two qualities — insipid, watery eyes and safety wear — tells parts of that story in the same way many “funny little men” (or FLMs) do: by melding workers with the products they make and by investing those products with NPC-like vitality.

It should come as no surprise that there’s a counter-history to that capitalist confusion, featuring public service mascots who advance ideas rather than objects: Reddy Kilowatt (1926), Smokey the Bear (1944), Mr. ZIP (1964), Officer Yuk (1971), Vince and Larry the crash-test dummies (1985), and so on. That’s all a pretty crude formulation of the problem, but that’s better than nothing. And considering the mind-bending cultural impact of mascots and other FLMs have had for several generations, that’s how much attention they’ve gotten: nill. That fact is curious in itself, as are the reasons for it — which, as Ambrose Bierce might have said, I shall attend to shortly.