(Orig to FB on 2025-12-19)

So…about that Epstein-related 120-page grand-jury document that was entirely redacted. The US has been through this, and we know how to do it — so please share this widely.

In the early 1970s, two government whistleblowers, Victor Marchetti (CIA) and John D. Marks (State Dept) wrote a book, The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence. The story of the legal scuffles around it are a bit byzantine, but the outlines are pretty simple:

For the first time ever, I believe, the federal government asserted complete prior restraint. The CIA convinced a court to issue a permanent injunction against Marchetti “requiring that anything [he wrote or said], ‘factual, fictional or otherwise,’ on the subject of intelligence must first be censored by the CIA” (1974, 1st ed., xiii).

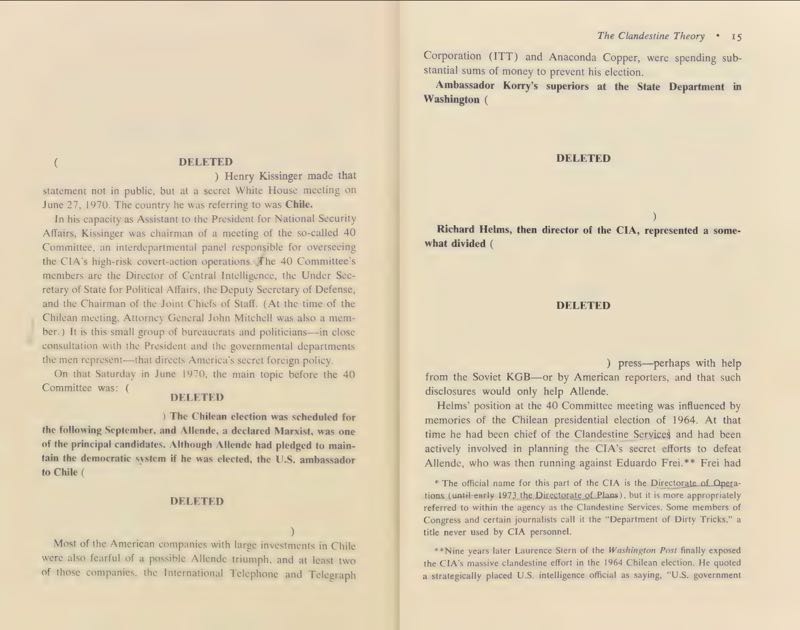

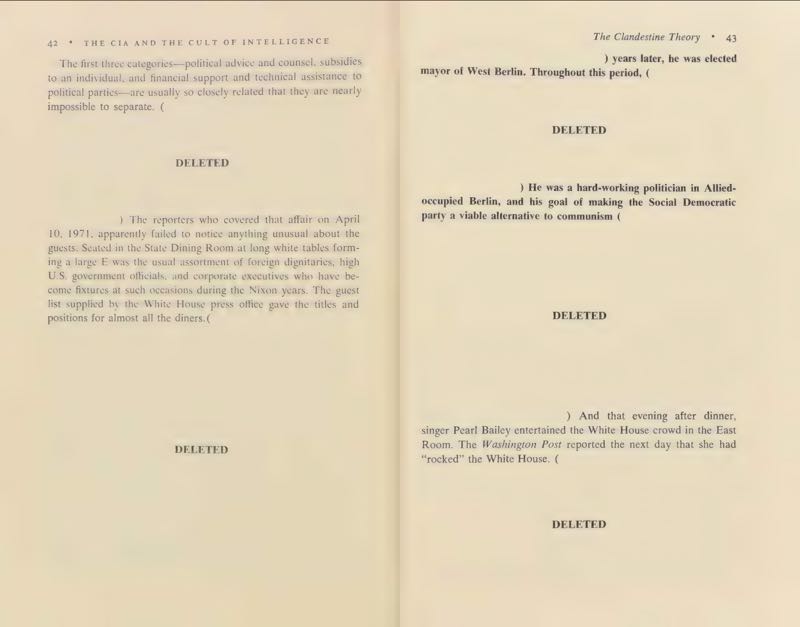

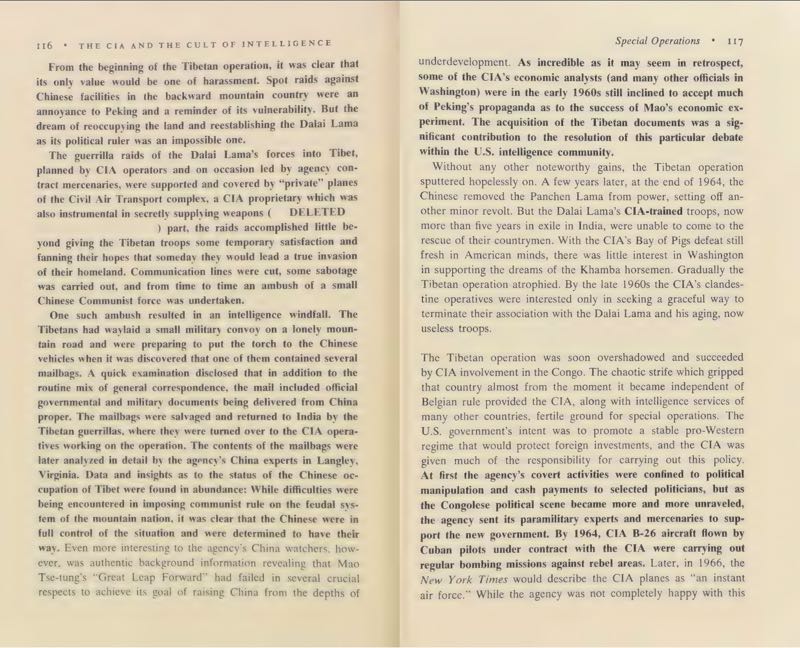

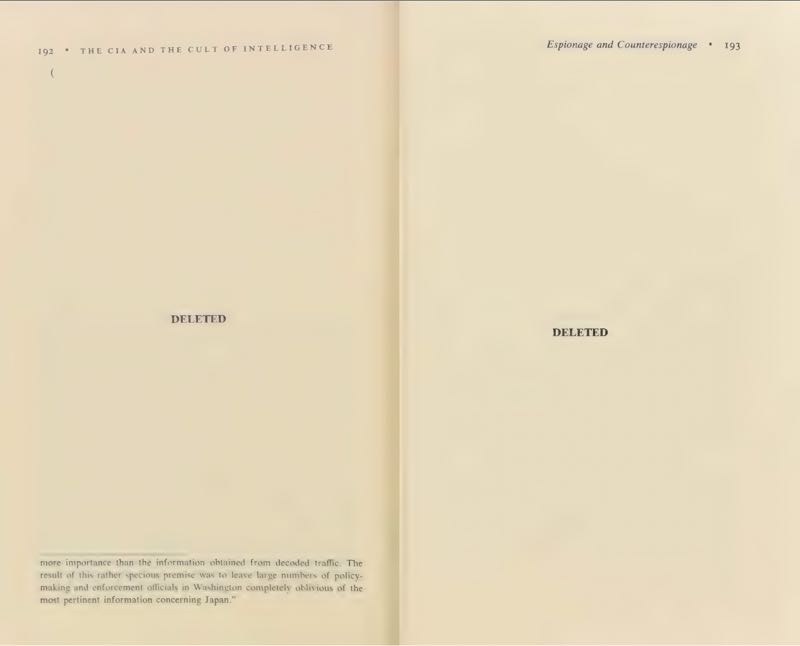

When Alfred A. Knopf signed the book, they sued the government to lift the injunction, causing the CIA to scale back its demands considerably, to around 350 sections. Each section was then adjudicated specifically. Knopf won most of them, but what they did next was brilliant — and should be seen as a high point in the history of book design. Passages the CIA won were left entirely blank: as you read the book, the text just stops, sometimes for pages. But passages the CIA lost were set in boldface.

The way forward here is to sue Bondi specifically over every. single. word. — including every if, and, and but. No court would agree to such a ridiculous waste of time, so the first thing they’d likely do is tell the DoJ to get serious and choose wisely.

The key here is that there’s a great deal to be learned from the process of prying these documents open. As we start to see less redacted versions of these documents, the changes will give us a clearer sense of what Trump, Bondi, and their minions are trying to hide. And that, in turn, will provider a better roadmap for journalists and other investigators to bring these scoundrels and conspirators to justice.

I’m way too young to have worked on Marks and Marchetti, but a few decades later I had the privilege of working for the New Press on a series of books by the National Secuity Archive. Like Marchetti and Marks, those books took an entirely novel approach to publishing materials — about the Cuban Missile Crisis, Iran–Contra, and US South Africa policy — that the US government had worked hard to suppress. Those books presented facsimiles of the original cables, memos, and reports along with critical introductions. At the time, that design-oriented approach was unheard-of, but it was a clear intimation of what we’ve since come to expect: direct access to documents. I mention this now because just last week, Bill Burr, a key figure at the Archive, passed away (link in comments).